Hurricane Oho by Mark Stone

October 2015. The rain eases slightly, and I glance at my GPS watch: 26.7 miles. "Today I have run farther than I have ever run before." As runners, how many times do we get to say that?

MemoriesWhen I was younger I don’t think I ever ran more than 7 miles. 5 miles was the upper limit of my typical runs. When I resumed running in 2009 I didn’t have any organized plan other than to get back in shape and return to a pastime that I loved. My first day out I covered a mile and a half at a slow jog, and I had to stop twice to catch my breath. I don’t even remember what prompted me to sign up for the Seattle 15K in spring of 2011, but I guess I felt that after two years of steadily improved running I needed a goal.

"Today I have run farther than I have ever run before."

My longest training run prior to the Seattle 15K was 8 miles, and that was farther than I had ever run.

The race itself, a beautiful course circumnavigating Lake Union in Seattle with an out and back leg in the direction of the Ballard Locks, was farther than I had ever run.

The race was an energizing, uplifting experience. I needed another goal, so I signed up for the Black Diamond Half Marathon in fall of 2011. My longest training run prior was 12 miles, and that was farther than I had ever run.

The race itself, starting and ending at Nolte State Park and looping through the farmland between the towns of Enumclaw and Black Diamond, was farther than I had ever run.

My time was a little over two hours, not bad for a 51 year old running his first half marathon. But I went out too fast, bonked pretty hard at the end, and knew I could do better. I spent the next 6 months working on shorter distances and improving my speed. Then I worked on maintaining that speed as I built stamina, aiming towards the Capital City Half Marathon in Olympia in May of 2012. Somewhere in April I cranked out a 15 mile training run, and again that was farther than I had ever run.

My Capital City time was very satisfying, coming in at 1:56:20. Daunting as it seemed, the obvious next challenge was a full marathon. I signed up for the Seattle Marathon, scheduled for November 2012. All summer and fall I trained, and in October I got in the first of the obligatory 20 mile training runs. That was farther than I had ever run.

Race day came, and again I went out too fast. My hamstring cramped up severely at Mile 14, and did not relent until Mile 22. I suffered terribly through the whole back half of the race. Yet in the mental battle to stay in the race and finish, I found myself encouraged from Mile 20 on by being able to say to myself that with each step I was running farther than I had ever run before.

26.2 miles. "Today I have run farther than I have ever run before." In the glow of that incredible moment, crossing the finish line in downtown Seattle, with a National Guardsman in full uniform congratulating me and putting a finisher’s medal around my neck, with my wife waiting right there to embrace me, in that happy moment I did not have the thought that would begin to creep up on me in the days and months ahead.

"Will I ever run farther?"

For a while I had no shortage of running goals. I wanted to set a new PR at the half marathon. It took me a couple of tries, but in October of 2013 at the Run Like Hell Half Marathon in Portland, I did. I wanted to run a full marathon where I didn’t bonk, where I could finish without feeling like I had utterly suffered. It took me a couple of tries, but in May of 2014 at the Capital City Marathon in Olympia, I did.

The finish line in Olympia was a great moment, with my youngest son and my wife right there. But it was also the first time in quite a while when I felt like I didn’t have a next running goal. At 54, I didn’t see myself getting a lot faster. And the older I got the more that I found road racing really beat up my body. Also, as part of my marathon training post-Seattle I had really taken to running in and around Mount Rainier National Park for my long runs. I had fallen in love with trail running. The solitude and sanctuary of nature that I loved from camping and backpacking came together with the deep, meditative state that I cherish on long, slow runs. Days running up on Mount Rainier were perfect days. So after Capital City I knew my next race had to be a trail race.

If we don’t fail at times in life then we aren’t really trying hard enough. We aren’t facing big enough challenges, we aren’t taking enough risks.

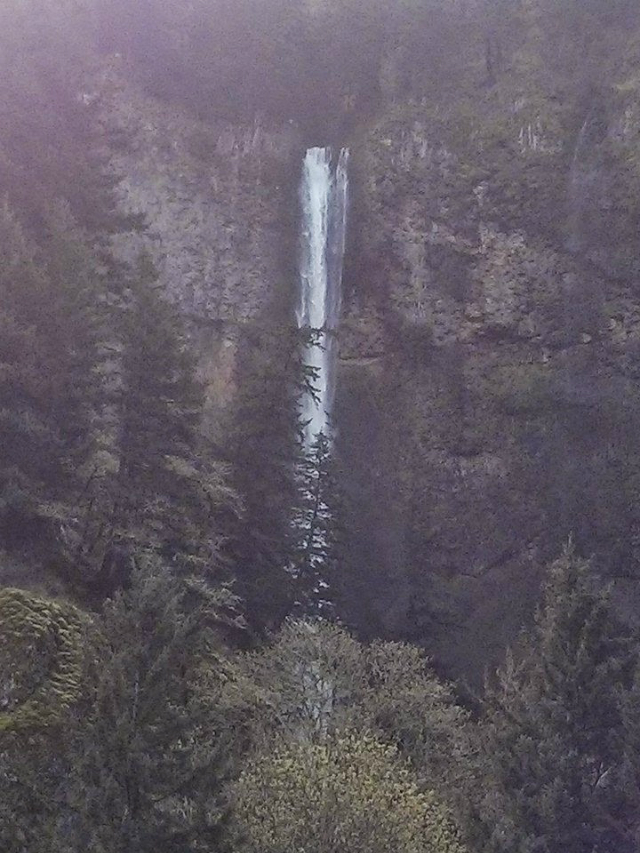

Rainshadow Running’s Gorge Waterfalls is arguably the signature race of the Pacific Northwest. Not as far as Western States 100, not quite the elevation gain of Pike’s Peak Marathon, but plenty challenging (the 50K has over 6000’ of elevation gain, the 100K over 12,000’), and a beautiful showcase of some of the most spectacular scenery in the Pacific Northwest. The course parallels the Columbia River climbing up and down the slopes of the Columbia Gorge, taking the runners past a series of waterfalls formed in the ravines running down the sides of the Gorge, including Horseshoe Falls, where the trail actually ducks behind the waterfall, and Multnomah Falls, the tallest waterfall in Oregon. With the course located less than an hour east of Portland, and within 3 hours of Seattle, the race is hugely popular and admission is by lottery.

I signed up for the March 2015 Gorge Waterfalls 50K. It should have been a great race. The weather was perfect, and I had the privilege of running with my friend Ken Ludt. Sometimes we never know quite what went wrong in a race. Was running 5 days a week in training instead of my usual 4 just too hard on my body? Or did I not run enough training miles? Were training runs with 3000’ feet of elevation gain enough? Or should I have done more hill work? Did I let the difficulty of the course intimidate me? (Perhaps.) Was it a mistake to eat or drink nothing through the first 9 miles of the race? (Yes.) Beyond marathon distances we are pushing the human body to the limits of what is possible, and so it does not take a big error for an entire race to unravel. At 24.5 miles I bowed out; a strong effort, but not as far as a marathon, and about the same distance as my longest training run.

So in April I again found myself without a clear running goal. I wanted to do a fall race, and I wanted to get more familiar with trail racing. Defiance 50K, scheduled for October 10, caught my eye. In addition to the 50K they also ran a 30K and 15K at the same time, and I found myself thinking that the 30K sounded like a good way to get in a decent trail race and work my way back towards another 50K attempt.

The WeatherOctober is usually a fabulous weather month in the Pacific Northwest. Temperatures have moderated, but the rainy season has yet to start. For runners this time of year promises blue skies and temperatures in the 50s to 60s, pretty much ideal running conditions. This year, however, is shaping up to be an El Nino year, meaning a longer and wetter rainy season, as well as more variance in conditions.

As October 10 approached the forecast appeared to settle in on cloudy, cool, with scattered rain showers. That didn’t phase me; I ran my first five races in the Pacific Northwest in at least partial rain.

Predominant high pressure systems over the North Pacific keep tropical storms at bay. Systems that form around Hawaii tend to blow towards the south and west. Occasionally Hawaii experiences something called Kona Winds, in which the prevailing wind direction reverses, sending storms to the Northwest. Generally these tropical depressions lose force as they move north, but on very rare occasions they gather strength, gaining storm strength after leaving the tropics. Scientists have had to coin the term "extra-tropical storm" for these, since technically they can’t be called tropical storms. Prior to 2015, the last time one of these made landfall in the Pacific Northwest was 1949.

So with less than a week to go until race day, I was a little alarmed to read news reports about something headed in our direction called Hurricane Oho. Centered around Ketchikan, Alaska when it finally made landfall the night of October 9, the storm would have wide ranging effects along the Alaskan coast, throughout British Columbia, and down into Washington and Oregon.

Point Defiance, where our race course was laid out, is a narrow, rugged spit of land that juts out into the water, dividing Puget Sound from Commencement Bay. Even in the best of times this stretch is notorious for high winds. Our forecast for race day was steady rain, winds averaging 15 MPH with gusts up to 50 MPH. My wife wondered if it might be prudent to take a pass on this race. But having taken a DNF in my previous 50K attempt I was determined to see this through, and no runner likes to waste months of training.

TrainingTo be clear, I didn’t really have a training plan. With my three marathons and most of my half marathons I’ve been very precise, working out a detailed week by week plan. For my 50K attempt in March I did the same thing. While I think it helped to have that discipline training through dark, wet, cold, winter months, I think I also felt a fair amount of training burnout by the time I got to the end of it. So for most of this year I’ve really just focused on running for the fun of running.

One of the best running decisions I’ve made was to buy an annual pass this year to the National Park system. I can be in Mount Rainier National Park in 40 minutes from my driveway, and the trails up there are spectacular. Where I run there are two main trailheads. One is all the way up at Mowich Lake, around 5000’ in elevation. From here one can follow the Wonderland Trail down the steep descent along Mowich River, or follow Wonderland in the opposite direction through Ipsut Pass and down the deep valley carved out by Ipsut Creek. Alternatively one can fork off the Wonderland Trail up to Spray Park, crossing 6000’ in elevation, with the snow cap of Mount Rainier so close you feel like you could just reach out and touch it.

The other trailhead is just past the Carbon River entrance to the park. You follow the Carbon River for 5 miles until you intersect with the Wonderland Trail at Ipsut Creek after it has tumbled down from Ipsut Pass. From here you have several choices for destinations: the steep climb up to Green Lake, the more gradual climb up to Carbon Glacier, or the intimidating ascent up Cataract Valley, taking you through the woods on endless switchbacks, across shale and loose rock as you leave the tree line, and finally into the snow line itself, well above 6000’.

Over the course of the spring and summer I ran all of these routes, running without regard for distance or pace, mainly just enjoying the scenery, immersing myself in nature, and just making sure I spent reasonable time on feet for my runs.

All this time I had it in my head that I was signing up for a 30K trail run in October. As August approached I increased the intensity of my runs, putting a bit more distance and elevation gain into my weekend long runs. Early in August I completed a 15 mile run along the Carbon River with about 2000’ of elevation gain. I realized that with a training run like that I felt completely ready for a 30K on flatter terrain. And I realized I was early. The race was still more than 2 months away.

On a whim, I pushed my training further. Long runs extended to more like 20 miles, often with 5-6 hours of time on feet, and elevation gain that was a minimum of 2500’. Yes, I was going for it. I was going to sign up for the 50K, and take another shot at the distance that had eluded me in March.

You have to finish because that’s where the car isTrail runners inevitably miscalculate. We make a mistake in planning, and sometimes we compound that with tunnel vision on the trail that leads to poor decisions, on rare occasions putting ourselves in jeopardy. I’ve been guilty of that a few times, and each time I tell myself "never again."

On September 5 I left the house pre-dawn, driving up to Mowich Lake. My intent was to run a classic route among local ultra runners called simply "The Loop". From Mowich Lake it climbs to Ipsut Pass, then drops all the way to the confluence of Ipsut Creek and Carbon River, then follows the river to just below Carbon Glacier before veering off to wind up Cataract Valley, emerging at Spray Park, and the descending back down to Mowich Lake. All told about 20 miles of the most gorgeous scenery anywhere in Mount Rainier National Park.

Since parts of this route were unfamiliar to me, I had picked up a trail map from the Park Service. Glancing at it before leaving the house, I read Ipsut Creek Campground as 4200’ elevation, and Spray Park as 4800’. So I assumed once I made the descent from Ipsut Pass I was looking at 600’ of elevation gain. There were several problems with this assumption. First, I had transposed the numbers when reading Ipsut Creek Campground; it’s actually at 2400’. Second, the 4800’ referred to Cataract Valley Campground, which is only part way up Cataract Valley. The ridge line summit of that section of trail is well above 6000’. So of course I only took clothing with me appropriate for a September run below the snow line: a long sleeve tech shirt and a light windbreaker.

The day started well. I’ve run the stretch up to Ipsut Pass many times, and I was eager to cross the Pass for the first time. I relished the steep descent on the other side, with it’s soaring, cathedral-like views of the surrounding cliffs. The flatter stretch along Carbon River was also familiar to me, and I’m always in awe of the sudden view of the summit of Mount Rainier after crossing Carbon River. By the time I reached the suspension bridge below Carbon Glacier I felt the exertion, but I felt in control.

The next three hours was a battle. I’d never been in Cataract Valley before, but it quickly became apparent that I’d wildly miscalculated the elevation gain on today’s course. This stretch alone was over 3000’ feet of climb, and it was unrelenting; never a step of level ground, never a step of downhill. The average grade along this section is greater than 10%. The mountain played head games with me, each ridgeline looking like it would be the summit, only to reveal itself as a shoulder hiding the next ridgeline beyond it. Somehow I kept going.

In the back of my mind it began to dawn on me that as the day wore on the temperature was actually dropping. I had long ago removed the windbreaker, soaked with sweat, and stashed it in my pack. As I left the treeline and moved into the clouds during my ascent I realized that the steady mountain breeze cutting through my damp shirt was chilling me. I couldn’t continue to divide my energy reserve between core warmth and exertion for the climb. I had to find a way to avoid crossing the line into even mild hypothermia.

I stopped, and pulled my windbreaker out of my pack. It was still soaked. Feeling the breeze, I played a hunch that it would dry quickly. I strapped it to the outside of my pack and kept running. About 15 minutes later I stopped again, and sure enough my windbreaker was dry. There was now snow on the ground all around me. Quickly I put on my windbreaker, and moved on. It worked. With a dry shell between me and the wind I felt the chill receding, and I felt more energy to push through the climb.

When I finally reached the summit ridge above Spray Park I was completely spent. Wobbly legs, light headed, queasy stomach; I had hit "the wall" and then some. Looking at the map, I could see that I had 7 miles to go. Even though it was mostly downhill at this point, I had no idea where I would find the strength to cover 7 miles. All I could do was tell myself, "No one is coming up here to help you down. So suck it up, buttercup; you have to finish. That’s where the car is."

I came out of the snow. I came out of the clouds. I mustered a crooked smile for the cheery day hikers making their way up from the other side. I caught the gleam of Mowich Lake through the trees. At last I found the car.

And for the rest of my training, and all through the looming battle that would be the Defiance 50K I never forgot that day. I had faced the mountain, and endured. If I could finish that run, I could do anything.

The CourseTacoma, Washington is not an obvious locale for a 50K trail run. Washington’s third largest city is a densely populated, mainly blue collar city wedged between Joint Base Lewis - McChord to the east and the Puget Sound to the west, straddling the hilly peninsula that splits Commencement Bay to the north from the main body of the Sound that passes to the west and south of the city.

At the very tip of this peninsula lies Point Defiance Park, 702 acres of old growth forest on the bluffs above Owen Beach and the rest of the waterfront. The forest has trees as much as 500 years old. Single track dirt trails criss cross throughout the park, feeling like high arched tunnels through the surrounding greenery. The trails occasionally burst out of the trees to an overlook offering spectacular views of the sweeping majesty of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, or the Vashon Island Ferry quietly plying the water between Point Defiance and Tahlequah. No section of the course is flat, but there are no long, sustained climbs either.

And Defiance 50K would not be what it is without Nelly’s Gnarly Descent, a quarter mile rough cut trail descending sharply from the bluffs to Owen Beach, and requiring three fixed place rappel lines to safely navigate the descent.

The race starts at Owen Beach, heading east along the boardwalk, before climbing a staircase to the bluff above and beginning the winding criss cross of dirt trails through the forest, before finally emerging at the base of Nelly’s Gnarly Descent for a short 100 yard dash to the finish line at Owen Beach. There’s a 15K that completes one loop of this course, a 30K that completes two loops, and the 50K that completes three loops.

There’s an aid station at the start / finish area at Owen Beach, and another aid station at Fort Nisqually around Mile 5. It’s net uphill, with lots of ups and downs, to Fort Nisqually, and an equally uneven net downhill back to Owen Beach.

Game DayIt’s a 45 minute drive from my house to Point Defiance Park, and when I depart at 6:30 AM gusting winds drive an angry mix of black storm clouds around the sky, broken up by streaks of blue sky. There is no rain. The temperature is 70F, about 20 degrees above the norm for October at that hour of the morning. I’ve been watching the Hurricane Oho reports closely all week, but as I near Point Defiance Park the blue sky increases. I’m starting to wonder if the storm already passed through over night.

I park at the Boat Launch. It’s a half mile from the starting line, but the course goes right by here, which enables me to use my car as a personal aid station. I lay out my fuel pack, my watch, my trail mix, and in a last minute decision pull off my windbreaker and long sleeve short in exchange for just a short sleeve shirt. I make the walk to the starting line, get checked in, and get my bib pinned on. By the time I’m done with all this we have only about 5 minutes until start.

I’m surprisingly calm. I don’t have a real race plan other than don’t start too fast, and while I feel confident in my training I know it’s been pretty informal by my standards. Still, I’m relaxed and ready at the start. The 15K, 30K, and 50K all start together, and so we have hundreds of runners gathered at the start, even though less than 100 of us are here for the 50K. After months of training in solitude, I enjoy the quiet camaraderie of all these runners gathered together ready to begin an endeavor together.

The horn sounds, and we start. I focus on staying in the back of the pack, thinking over and over in my head, "Don’t start too fast." Nonetheless, the first two miles goes by quickly.

Then the rain starts. At first, it’s just a drizzle, more heard than felt as the gentle patter quietly cascades through the treetops. As we approach Mile 4, the sky opens into a downpour. I’m soaked, but I feel elated. It’s warm, and the air smells fresh, and I’m surrounded by enthusiastic runners. We are Pacific Northwest runners. This is what we train for. This is what we train in. Realizing that my shirt is only weighing me down at this point, I duck into a covered picnic area, strip off and wring out my shirt, and stuff it in my fuel pack. I run the rest of the first loop topless. There will be a price paid for this in chafing against my fuel pack straps, but that’s a future problem. In the moment I don’t care.

About a mile from Fort Nisqually we reach a steep uphill that runs some 300 yards. The downpour has unleashed a mini flash flood coursing down the trail here, and the pack of us has no choice but to plunge in and slog our way up. About halfway up I hear panicked cry of "I’m not going to make it!" from the woman behind me. Glancing over my shoulder I see her standing there just paralyzed. She’s wearing a large brace on her right knee. She looks up at me and says, "My knee. I don’t think I can do this." I reach down, clasping her arm, and try to say with as much calm as I can muster, "Come on. We’re all in this together." Between the mud, and the torrent of streaming water, my own purchase is far from secure. Hand in hand, step by step, she and I make our way to the top of this stretch until the terrain flattens, and water ebbs, and it’s possible to run again. She flashes me a thankful smile, I give her a thumbs up, and take off up the trail.

Fort Nisqually is a gorgeously restored 19th century wooden palisade fort, a classic example of the trapping and trading outpost so common to the early European settlers in this region. On the other side of the grassy field behind the fort is the small pavilion tent that marks the aid station. Taking another lesson from past races, I am drinking water early and often, and snacking on my trail mix early and often. I opt not to stop at the aid station, and plunge into the forest once again. The next section presents a lot of short, steep hills with a winding trail, and dirt that has not quite turned to mud. After a couple of miles the trail widens, but also frequently fills with puddles. There’s no longer any point in dodging them, and this stretch is mostly downhill, so I just charge straight ahead through the rain and the puddles on the most direct path I can find.

By the time I reach Nelly’s Gnarly Descent the rain has tapered back down to a drizzle. I stumble through the first couple of switchbacks due to the mud, and at one point the only way I can brake my descent is to crash into and hug a tree trunk. Then I reach the rappel lines. I navigate the first two successfully, and I’m feeling pretty proud of myself. Then right at the base of the third line my feet go out from under me, and down I go. As I reach Own Beach and the finish area both hands are covered in mud and I have a long muddy streak that extends all the way from my hip to my left ankle. Fortunately there’s a sink at the finish area, and I wash up as best I can. I glance at the clock, and the happy 15K runners who are crossing the line and done for the day. 1 hour 45 minutes. Much faster than I need to be to stay ahead of the 8 hour cut off time. Quickly I move out to start the second loop, and more importantly get to my car half a mile away.

I spend 20 minutes at the car. Huddled under the raised hatch in the back to stay somewhat dry, I do a complete change of clothes, except for my wet shoes, putting on something dry from head to toe. I swap in a fresh pack of trail mix, check the water level in my fuel pack, and set off.

The rain has mostly stopped. Patches of blue sky are visible. It remains this way for most of Loop 2. This time around, everything feels quiet. Instead of being surrounded by a crowd of eager 15K runners, I am mostly running in solitude. I glance an occasional 30K or 50K runner through the trees, but mostly I am nestled deep into the serenity of quiet trails through old growth forest. Now that the ground has absorbed the rain, the mud is much worse. The hilly switchbacks after Fort Nisqually have become treacherous; to keep my footing I have to take the downhills even slower than the uphills. I mud ski down the last of these, and the course opens up once again to wider, flatter trails.

A few minutes later, around Mile 18, I spot another runner up ahead, steadily walking along. I’m feeling fatigued, but not spent, trying not to think about the fact that I still have a half marathon to go. I pull up next to her, and slow to a walk. Her name is Kathleen, and she is also signed up for the 50K. I ask her how she’s doing.

She smiles grimly and says, "I think I’m dropping out at Mile 20. Today just isn’t my day." She pauses, and continues, "I’ve had a pretty aggressive summer of racing, and my knee has been acting up. The mud has been really hard on it today, and I don’t want to push too much. This is just a training run anyway."

A note to all you non-runners: that last statement is a lie. Yes, we runners often work a scheduled race into our training plans where the training goal is a different race. But come game day, we are all the same. We all want to compete, we all want to give our best effort. There are no "training runs" on game day.

Kathleen and I walk and chat for a few minutes, swapping stories about races and courses in the area. I listen with interest as she talks about trail running on Mount Hood, and she expresses genuine interest in the Winthrop Marathon and the North Cascades area generally. I wish her well, urge her to be careful, resume running, and move on. I feel some reluctance; it’s been lonely out here on Loop 2, and just having Kathleen to talk to has lifted my spirits. Perhaps I have done the same for her. I won’t know for several days yet when results are posted, but Kathleen will in fact finish. A mere 7 minutes head of the cutoff time, but a finish nonetheless. Game day. There are no training runs.

This time I navigate Nelly’s Gnarly Descent more gracefully, making it to the bottom without a fall. The rain is starting to pick up again. I wave to the volunteers as I pass the finish area and begin Loop 3, the final loop. It has taken me 2 hours 45 minutes to complete the second loop, almost an hour longer than the first. With the 20 minute car break and the walking time with Kathleen that isn’t too surprising. I am moving more slowly overall, but I’m still well ahead of cutoff pace. Back at my car I take a shorter break this time. I spend about 10 minutes changing into dry clothing from the waist up and then I’m on the move again.

Farther Than EverI am tired. But I also know that I have banked enough to time complete the final loop at a moderately brisk walk, if need be. It’s the last loop, and as far as I know I am DFL ("dead f’ing last" in running vernacular). In the next mile or so I catch up to two women running together. They look relaxed, keeping a comfortable pace and quietly chatting. They step aside for me as I close to them, and I smile and nod and move on. On the longer straight stretches I can see two men up ahead of me, and they appear to be switching back and forth, jockeying for position. We’re still on the uphill portion leading to Fort Nisqually, and so I’m wary of pushing too hard to try and close with them.

Abruptly the sky darkens, and the temperature drops noticeably, and the sighing wind explodes into a howl. The sky opens, and the rain comes down in torrents. The rain is literally blowing sideways, and I can barely see more than a few feet in front of me. The wind is so loud I can’t hear myself think. The wrath of the wind takes its toll on the forest. I am pelted by pine cones knocked loose; I see branches down on the trail; I hear the crashing of tree limbs newly torn free by the storm. I am completely soaked through, and the temperature is no longer warm enough for me to shrug it off. The force of it all has left me shell shocked. For the next couple of miles the storm has me beaten down to a basic animal level where all I can do is shuffle forward one step at a time, sometimes running, but just as often walking.

Eventually the thinning of the trees tells me I’m approaching Fort Nisqually. Dimly I wonder if they might call the race for safety reasons at this point. Part of me wonders if I’d be grateful, but the louder voice in my head fiercely says, "No!" I will finish this course, on my own if I have to.

The wooden palisade wall of the fort provides brief respite from the wind. Indeed, as I reach the field beyond the wind has died down, though the downpour continues unrelenting. I reach the aid station, and this last time through I am ready to take a break. I spend a few minutes chatting with the women who are volunteering at the aid station, and giving them a truly heartfelt thanks. These are horrendous conditions to be outside, and they have only their small tent canopy for cover. At least I can keep moving to stay warm.

One thing I’ve learned over the years is that, at this stage of a race, I should abandon any preconceived notions of what I’ll rely on for fuel and simply listen to my body. The urges that sweep over me are always amusing and surprising. Today is no exception. "Mountain Dew? This stuff is amazing! Pretzels? Perfect! How many can I take?" I also discover that my fuel pack is now empty, and the volunteers help me refill it.

As I’m pulling out of the aid station I see the two women behind me rounding the corner of Fort Nisqually and heading across the field. A little over 25 miles done. A little over 5 miles to go. One last time I descend into the hilly switchbacks and the mudfest that awaits. I get occasional glimpses of one of the men ahead of me as he steps gingerly through the mud.

Somewhere in the next few miles it dawns on me that I haven’t really hit "the wall." Yes, I’m fatigued. No, I don’t have a lot left. But I feel nothing like the crushing psychological darkness that descended on me in my first two marathons. I’ve experienced nothing like the rubber-legged, light headed wooziness with which I stumbled through my last couple of miles at Gorge Waterfalls 50K before, muscles literally feeling like they were on fire, I dropped out just before Mile 25. The confidence I’ve nurtured all day is swelling up inside me around a rock hard, solid core of determination. I’m going to make it. I’m going to finish. I am an ultra runner. Then I look down at my watch.

26.7 miles. "Today I have run farther than I have ever run before." As runners, how many times do we get to say that? Suddenly I am weeping. All the emotions have bubbled over, and I am standing in the middle of trail sobbing openly. This is the part of distance running, the spiritual challenge, that is so hard to explain to non runners. 27 miles in, and you have no energy for anything, except to be utterly and completely who you are, stripped down to the most naked essence of your soul.

And then I am running. I don’t even know how. Not walking, not shuffling along, not jogging, but flat out running, faster than I have run all day. And it feels effortless. The trail has widened, turned mostly downhill, and I am bounding down the trail, through the rain, through the puddles, with a lightness that is normally reserved for my dreams.

I catch the guy in front of me just as we reach a road crossing, and we are greeted with the bizarre sight of a traffic jam. He glances at the front of the line of cars and says, "Tree down." I follow his stare, and sure enough a massive tree has fallen across the road. I think of everything Hurricane Oho has thrown at me this day -- the lashing rain, the howling wind, the downed branches, the mud. I think to myself, "Oho, you have challenged me, but nothing has tested me like Mount Rainier." I think back to that day, only a month ago, standing above Spray Park in the snow, me cold and spent from the grueling ascent up Cataract Valley. I feel for where I had to dig down inside myself that day, and realize that day has made me ready for today, for I do not have to dig that deep. I look now at the storm around me and feel capable and defiant. Crossing the road, I take off at a dash, leaving the other runner behind me.

The euphoria subsides, but never completely goes away. My pace eases, but I’m still running hard. I relish the rain on my face. I eagerly seek out every puddle. About a half mile down the trail I catch the other guy. As I flash past him, I call out, "Hell of a day for a run!" I’m sure the grin on my face was ear to ear. He just looks at me like I’m crazy. In that moment, I probably am. When I emerge from the trees to the top of Nelly’s Gnarly Descent I’m almost sad. As with reading a cherished book, part of me doesn’t want this race to end.

I make my way, one last time down the rappel lines, and for the first time since the Fort Nisqually aid station I am conscious of just how fatigued I really am. I simply haven’t the strength to stay on my feet through this descent. The last 20 feet is just a slide on my butt. Then it’s done. Muddy, bloody, and sweaty, I stand with 100 yards of waterfront boardwalk between me and the finish line. Pride conquers fatigue, and I run. I hear people cheering in the rain, and the finish line volunteer calling out my name, and I am grateful for the rain for a whole different reason. The tears are back, but on my rain streaked face as I cross the finish line no one seems to notice.

7 hours, 27 minutes, 57 seconds. 31 miles, run and done. I may never get to say it again, but I can say it now: today I have run farther than I have ever run before.